News

News Archive

- ‘Amid the Hills of Redesdale’ community radio play released!

- A Fantastic Year for Redesdale!

- Archaeological Excavation report produced for Bellshiel

- Archaeological Excavation report produced for Yatesfield enclosed settlement

- Archaeological Survey Report Published For Ancient Settlement At Rattenraw

Thomas Sharp’s Forestry Villages: Kielder, Byrness and Stonehaugh

March 1, 2022

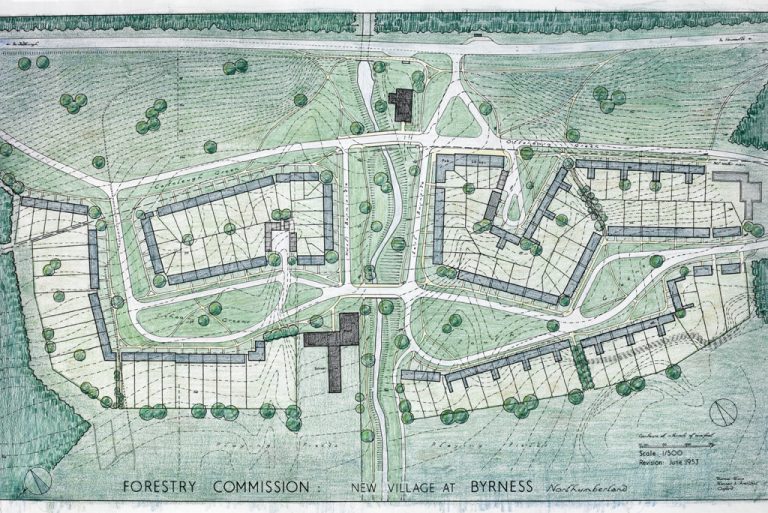

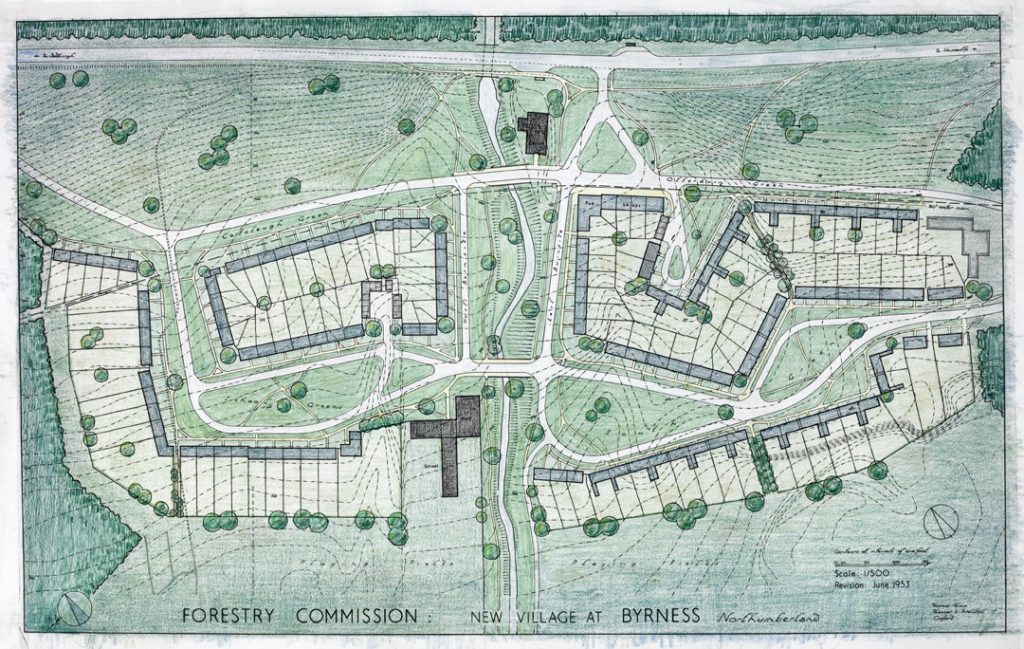

As the forestry industry grew in the early twentieth century, so did the demand for accommodation for forestry workers and their families. One such village was Byrness in Redesdale.

John Pendlebury, Professor of Urban Conservation at Newcastle University, has kindly given us permission to reproduce his article for the Northumbria Gardens Trust about the forestry villages of Kielder, Byrness and Stonehaugh, planned by Thomas Sharp.

Thomas Sharp was a planner and writer of some significance in the middle part of the twentieth century, although he was never in the mainstream. A native north-easterner, raised in fairly humble circumstances on the south-west Durham coalfield, his was an impressive rise in the profession; all the more so due to his tendency throughout his working career to fall out with people! His first polemical text, Town and Countryside, published in 1932, was in part written whilst unemployed as the result of one such falling out. In very brief summary, Sharp celebrated the planning achievements of the Enlightenment period for creating harmonious towns and beautiful countryside. These were inspiration not for imitation but for planning in a contemporary way; for example he believed in a clear separation between town and country and was very scathing about the contemporary planning ethos, originating in garden-city ideas, which created low density suburbia. The way of building in the countryside was not through ribbon development and sprawl but through creating new villages.

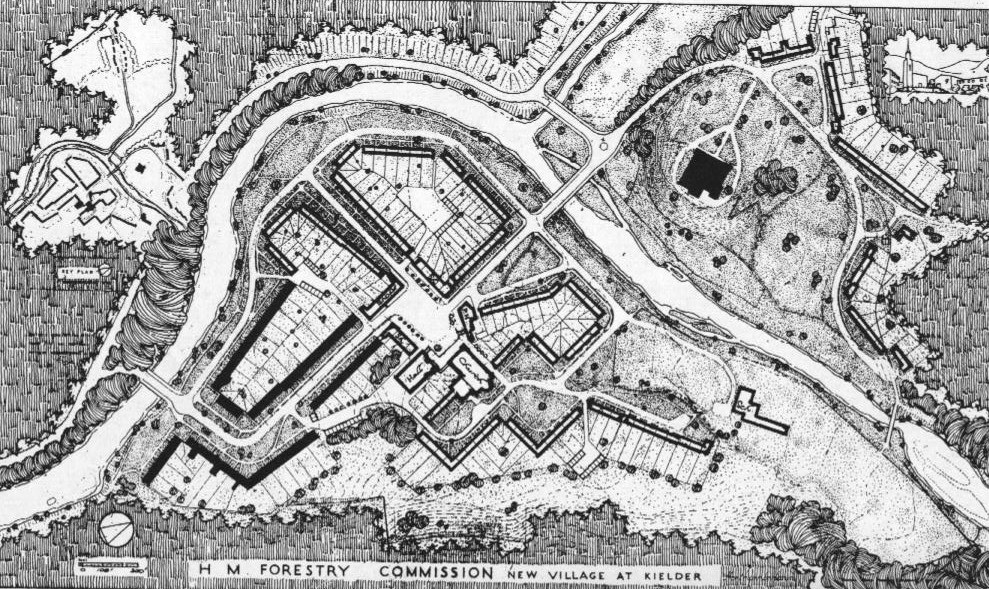

His work in the north-east was primarily in Durham and for the Forestry Commission. In Durham he produced the well-known 1945 plan Cathedral City (part of a slew of such plans he produced at this time for historic cities including Oxford, Exeter, Salisbury and Chichester) and he was employed by the City as consultant advisor for many years subsequently. For the Forestry Commission he was initially engaged in 1946 to masterplan eight villages for its forestry workers (ten had initially been suggested), each of which would house between 350 and 500 people. The forests of Kielder, Wark and Redesdale were undergoing massive expansion and it was anticipated a large workforce would be needed close by. Sharp and others argued that rather than scattered small groups of houses, which had been the policy of the Forestry Commission up until that time, houses should be grouped into villages of sufficient size to sustain community facilities. This was to be a phased work; the Commission decided they immediately needed 150 houses which Sharp recommended be divided between three sites; Kielder (60 houses, adding to some earlier inter-war semis), Byrness (50 houses) and Stonehaugh (45 houses); though these settlements would be incomplete he considered that they would be of sufficient size to give some community and village character.

| Area | Village | No of dwellings | Notes |

| Kielder | Kielder | 200 | |

| Plashetts | 100 | Low priority, site now under reservoir | |

| Mounces | 100 | Low priority, site now under reservoir | |

| Comb | 300 | ||

| Chirdon-Bowen | 100 | ||

| Wark | Stonehaugh | 300 | |

| Redesdale | Rochester | 80? | Long-term village expansion |

| Byrness | 120 |

There were already a number of buildings at Kielder. The castle of course, but also various houses, some built in the inter-war period for the Forestry Commission and mostly located in the Kielder Station area. Though Kielder was an obvious place to develop a village at the outset it was seen to be challenging because of the scattered and disparate existing buildings. There was a debate over whether village extension should take place around the station but Sharp was firmly of the view that it should be on the new site of Butteryhaugh (though there is in practice also some post-war development around the station). The completed plan would have established a more satisfactory visual relationship with the castle than exists today – Sharp orientated one of his informal spaces at the entrance to Butteryhaugh to capture the view up the hill. Byrness and Stonehaugh were virgin sites. Comb was to have been the fourth village, again a virgin site, with a linear plan running along an isolated ridge in the Tarset Valley.

In undertaking his designs Sharp was mindful of his own writings on villages, particularly in his classic 1946 text The Anatomy of the Village and his conclusion that most English villages, especially in the north, have a strongly nucleated form. At the same time he strove for a reasonably organic and non-formal plan, without axial treatments and so on; a kind-of ordered informality. So Sharp planned terraces (he was a great believer in terraces and streets) with occasional semi-formal spaces and focus on community buildings. Building in stone was not possible so he proposed white or near-white colourwash as a finish. In Sharp’s view the frontage of properties was essentially part of the public domain. The modest front gardens in front of houses were to be left open and grassed as part of the wider composition. Private space was to be found in the long rear gardens.

Like so many of Sharp’s commissions things were not to work out as he wished; indeed in his unpublished autobiography, Chronicles of Failure, he goes as far as saying that the Forestry Commission was the worst client he had! This had been an important project to him, ‘I felt that what would most satisfy me in life, what would most justify me ever having lived, what would crown a whole life’s work, would be to build a good new village and write a good, even if very short, lyrical poem’ (p247). Though he was not architect for the houses built he was not unhappy with these (these were by Robert Mauchlen of Mauchlen & Weightman). Rather, the problem was that the works were not continued, as the mechanisation of forestry work and improving communications meant that the scale of workforce estimated to needed on site dropped rapidly. Kielder and Stonehaugh were only ¼ to 1/3 completed – Byrness rather more so and Sharp felt it rather more successful as the part that was constructed was more self-contained – the remainder of the village would have been the other side of a stream (Sharp’s favourite was perhaps Comb, abandoned all together). Furthermore, the Forestry Commission refused to provide the necessary community buildings including basic needs such as a shop or pub and he was often unhappy with details such as bridges. Only after much pressure did they provide £5 or so per village for amenity tree planting!

Visiting the three villages today, the overall planning of the parts that were built, in terms of the combinations of buildings and the spaces that link them, stands up fail well in my view. One suspects, though, that Sharp would not have been too impressed with some of the attempts to personalise both houses and the gardens to the front. At the same time understanding something of the history explains what is so unsatisfying in each case – they are fragments, in the cases of Byrness and Stonehaugh little more than a series of terraced houses, not the complete and coherent villages Sharp wanted. The experience is perhaps most dispiriting at Kielder, however. For at Kielder further development has taken place and rather than using the Sharp plan as a key for growing the village the building has been haphazard and unrelated to what went before, architecturally, but more importantly in terms of siting.

John Pendlebury

Bibliography

Sharp, T. (1932). Town and Countryside: Some Aspects of Urban and Rural Development. Oxford, University Press.

Sharp, T. (1945). Cathedral City: A Plan for Durham. London, Architectural Press.

Sharp, T. (1946). The Anatomy of the Village. Harmondsworth, Middlesex, Penguin.

Sharp, T. (1953). “The English Village.” Design in Town and Village, T. Sharp, F. Gibberd, and W. G. Holford, eds., HMSO, London, 1-19.

Sharp, T. (1949). “Village Design.” Journal of the Town Planning Institute, 35(5), 137-148.

Sharp, T. (c. 1973). Chronicles of Failure. GB 186 THS. Newcastle upon Tyne: 296.

Stansfield, K. (1981). “Thomas Sharp 1901-1978.” Pioneers in British Planning, G. Cherry, ed., The Architectural Press, London, 150-176.

This article also draws upon the Special Collection of Sharp papers, Newcastle University. This collection is currently subject to an AHRC Resource Enhancement Grant.

Leave a Reply